[This Washington Post story highlights important limitations in current voice assistants that lead to frustrating interactions, though arguably more negative rather than fewer medium-as-social-actor presence experiences. See the last two paragraphs for an interesting theory about what’s happening. For a more optimistic perspective on these technologies and how social cues can be used to improve their effects, see the January 2022 MIT News story “’Hey, Alexa! Are you trustworthy?’: The more social behaviors a voice-user interface exhibits, the more likely people are to trust it, engage with it, and consider it to be competent.” –Matthew]

[Image: Credit: Washington Post illustration/iStock]

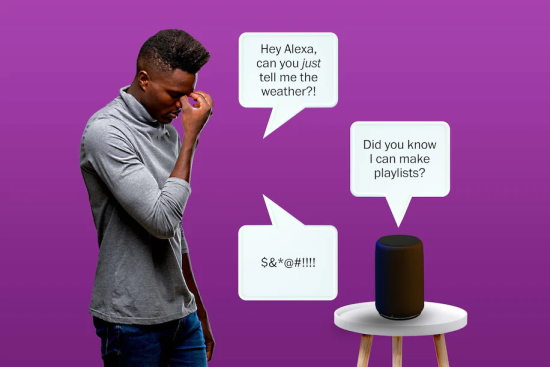

Needy, overconfident voice assistants are wearing on their owners’ last nerves

Nobody needed another difficult family member. Alexa and Siri showed up anyway.

By Tatum Hunter

March 7, 2022

Kate Compton can talk to her Alexa voice assistant about three things: music genres, radio station call signs and the time of day. Stray from those safe topics, and the consequences could be dire.

“Hey Alexa, play ‘Despacito,’” Compton said into the ether from her home in Evanston, Ill., where she teaches computer science at Northwestern University. A nearby smart speaker launched into an explanation: The Luis Fonsi song was not available, but it could be if Compton paid for a subscription. Alexa proceeded to walk us through the pricing plans.

Compton tried again: “Hey Alexa, play classical music.”

“Here’s a station you might like,” Alexa said tentatively, adding that the songs were hosted on Amazon Music.

Americans welcomed voice assistants into their homes on claims that Siri, Alexa and Google Assistant would be like quasi-human helpers, seamlessly managing our appointments, grocery lists and music libraries. From 2019 to 2021, the use of voice assistants among online adults in the United States rose to 30 percent from 21 percent, according to data from market research firm Forrester. Of the options, Siri is the most popular — 34 percent of us have interacted with Apple’s voice assistant in the last year. Amazon’s Alexa is next with 32 percent; 25 percent have used Google Assistant; and Microsoft’s Cortana and Samsung’s Bixby trail behind with five percent each.

(Amazon founder Jeff Bezos owns The Washington Post.)

While use is on the rise, social media jokes and dinner-party gripes paint voice assistants as automated family members who can’t get much right. The humanlike qualities that made voice assistants novel make us cringe that much harder when they fail to read the room. Overconfident, unhelpful and a little bit desperate, our voice assistants remind us of the people and conversations we least enjoy, experts and users say.

As Brian Glick, founder of Philadelphia-based software company Chain.io, puts it: “I am not apt to use voice assistants for things that have consequences.”

Users report voice assistants are finicky and frequently misinterpret instructions.

Talking with them requires “emotional labor” and “cognitive effort,” says Erika Hall, co-founder of the consultancy Mule Design Studio, which advises companies on best practices for conversational interfaces. “It creates this kind of work that we don’t even know how to name.”

Take voice shopping, a feature Google and Amazon said would help busy families save time. Glick gave it a try and he’s haunted by the memory.

Each time he asked Alexa to add a product — like toilet paper — it would read back a long product description: “Based on your order history, I found Charmin Ultra Soft Toilet Paper Family Mega Roll, 18 Count.” In the time he spent waiting for her to stop talking, he could have finished his shopping, Glick said.

“I’m getting upset just thinking about it,” he added.

Then there are the voice assistants’ personalities. Why does Google Assistant confidently say “sure!” before delivering a “bafflingly incorrect” response to a request, Compton asked. Why is Alexa always bragging about her capabilities and asking if you’d like her to do extra tasks, TikTok creator @OfficiallyDivinity wonders in a video. She accuses Alexa of being a “pick me,” a term for women willing to step on others to get approval. The clip has more than 750,000 views.

Voice assistants have become punchlines, and their makers are to blame, says Hall. In the rush to get voice assistants into every home, she argues that companies didn’t stop to consider whether they were setting expectations too high by pitching these chunks of software as human-ish helpers. They also didn’t think about which tasks actually make sense to do out loud, she said.

For instance, online shopping freed us from unnecessary interactions with human employees, Hall said. With voice shopping, companies added that friction right back in. Nobody likes chatting about the number of toilet paper rolls in a pack.

An Amazon spokeswoman said that Alexa may “occasionally highlight experiences or information” consumers might find useful and they can turn off certain notifications in the Alexa app under settings.

She said shopping features on Echo devices are “incredibly popular” and use is growing “significantly” year over year, without providing specific figures.

She added that Alexa’s understanding has improved significantly, despite increasingly complex requests from users.

For its part, Google says it’s investing in the Assistant’s language understanding and speech technology to help it better deal with nuance and respond in a natural way. An Apple spokeswoman said Siri’s core functions have gotten considerably better in the last few years because of advancements in machine learning.

But there’s a deeper emotional problem at play, says Compton, who built the AI that powers Twitter bots like Infinite Scream and Gender of the Day. In developing voice assistants, she says companies ignored the often unspoken rules of human small talk. We use small talk to show other people that we’re on the same wavelength — it’s a quick way to signal, “I see you, and I’m safe,” Compton said. According to philosopher Paul Grice, effective chatter must be four things: informative, true, relevant and clear.

Alexa’s comments are often none of those, Compton said.

“Our vision is to make interacting with Alexa as natural as speaking to another person, and we’re making several advancements in AI to make this a reality,” the Amazon spokeswoman said.

Still, users say awkward exchanges make us feel bad for Alexa — soulless, trapped in a smart speaker and desperate to be helpful. According to Compton, we end up feeling bad about ourselves as well, since conversations require two parties and a failure by one feels like a failure by both. Even if the sheer difficulty of developing conversational AI were the only thing to blame, bad interactions with voice assistants make us feel broken, too.

“Every time we talk to one of these things, we feel like we’re bad at it,” Compton said.

|